Many centuries ago, a fish passed away and was interred in sediment which over time resulted in fossilization. Presently, after 319 million years have elapsed, it has been the focus of research which discloses “the most ancient instance of a properly conserved vertebrate brain.”

The research, which has been published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, was headed by Rodrigo Figueroa, a doctoral student at the University of Michigan. The species studied was a ray-finned fish called Coccocephalus wildi. Ray-finned fish, including swordfish and trout, are a varied group comprising approximately 30,000 species.

Enlarge the image.

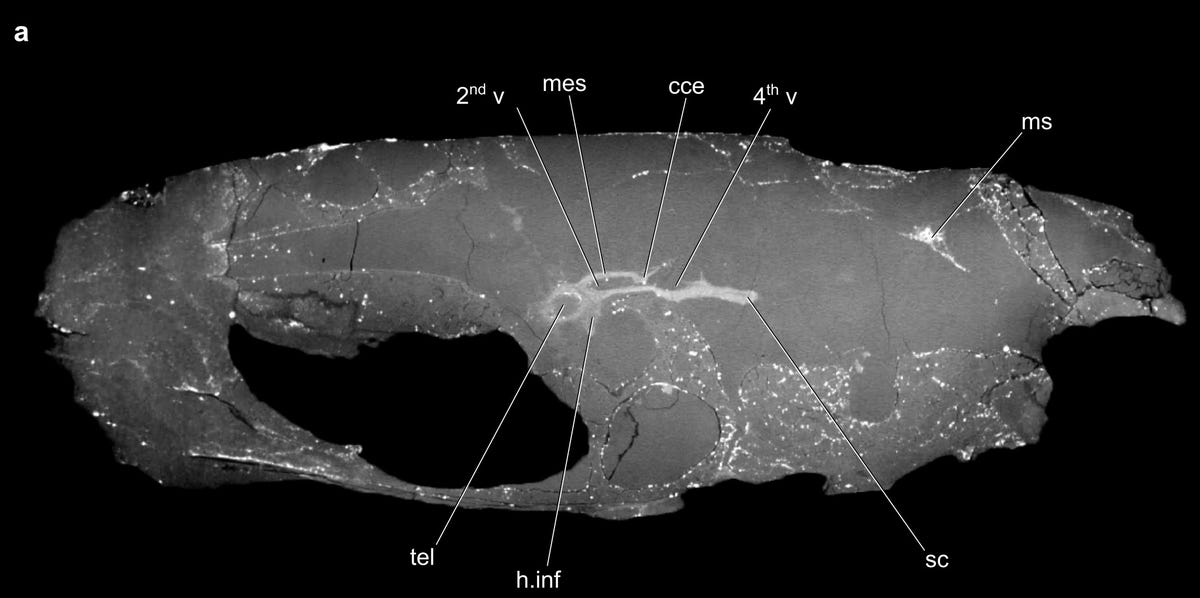

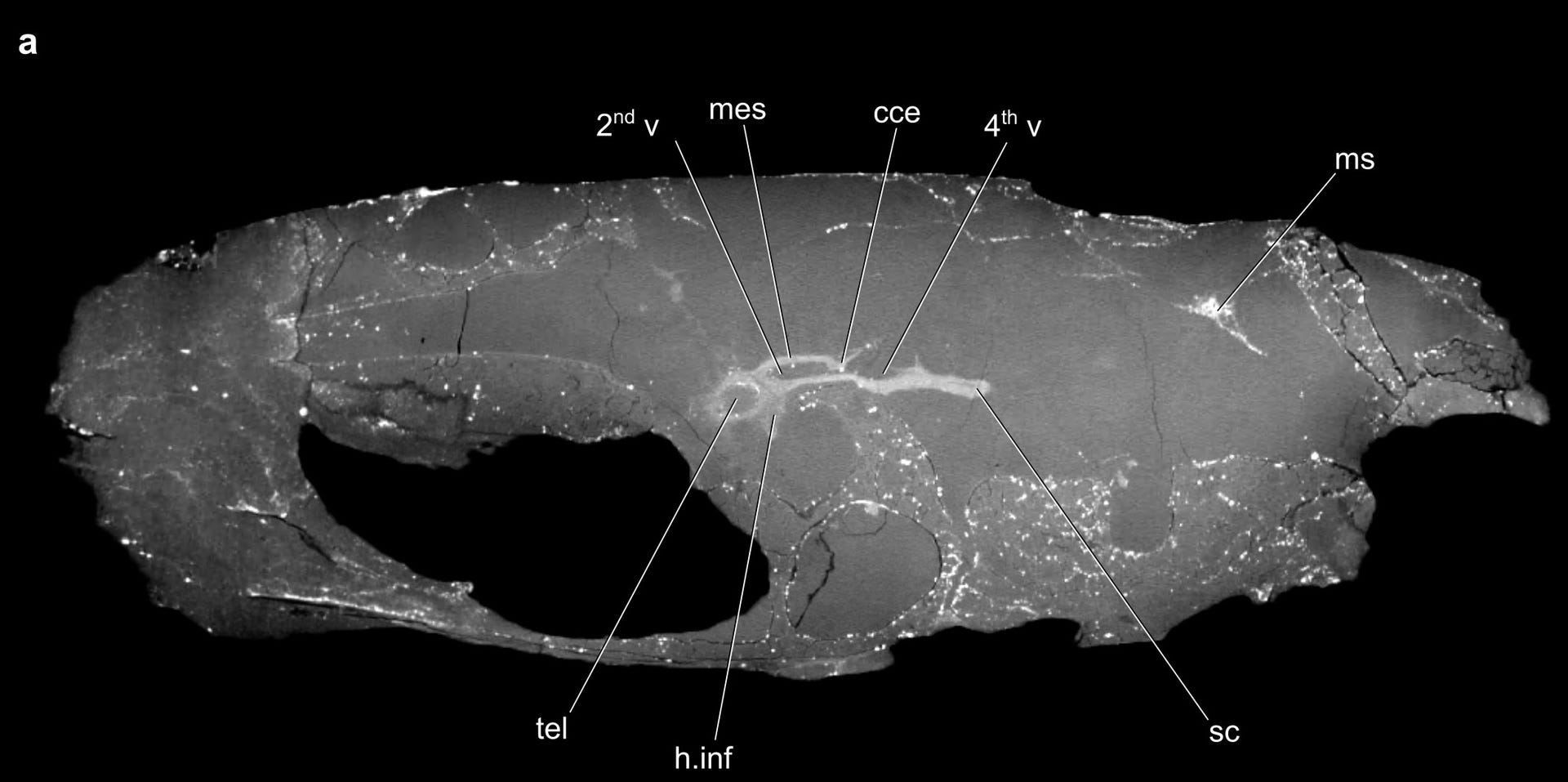

The external appearance of the fossilized skull of Coccocephalus wildi may appear unremarkable. However, according to a statement from the University of Birmingham, paleontologist Sam Giles, who is one of the study’s co-authors, stated that the unexpected discovery of a vertebrate brain preserved in three-dimensions has provided an astonishing understanding of the neural anatomy of ray-finned fish. The findings reveal a more intricate pattern of brain evolution than what is suggested solely by observing present-day bony fish, thereby enhancing our ability to precisely determine the evolution process and timeline for these fishes.

By utilizing a noninvasive CT scan, which is also implemented in medical imaging for humans, the scientists were able to examine the interior of the skull without causing any harm to the fossil. The scan revealed a one-inch (2.5 centimeters) brain and cranial nerves. According to the university, a dense mineral took the place of the brain and nerves, resulting in their preservation with exceptional precision.

Resize Picture

A CT scan image of the Coccocephalus wildi skull from the paper is shown, with lines indicating internal parts of the brain. While fossilized bones are common, preserving soft tissues like brains is rare. Comparing the structure of the ancient brain with those of modern-day animals, researchers found that, unlike current ray-finned fish whose brains fold outward during embryonic development, Coccocephalus’ brain folds inward. This discovery sheds light on the timeline of brain evolution in ray-finned fish.

According to Giles, the brain of Coccocephalus wildi has similarities to those of paddlefish and sturgeon, both of which are classified as “primitive” fish due to their divergence from other ray-finned fish more than 300 million years ago.

The fossil was initially discovered in an English coal mine more than a hundred years ago. According to Figueroa, “Given the widespread accessibility of contemporary imaging techniques, I wouldn’t be surprised if we discover that fossilized brains and other delicate structures are more prevalent than we previously believed. Our research team and others will now examine fossilized fish heads from a fresh and unique viewpoint.”