Although it may seem unthinkable that surgeons could perform the intricate procedure of brain surgery without advanced modern medicine, historians have repeatedly demonstrated that its origins date back thousands of years. In fact, there are those who argue that neurosurgery may be the oldest “specialty” in the history of medicine.

For example, archaeological excavations have unearthed and interpreted ancient Egyptian papyri that discuss techniques for stitching skulls and the understanding of cerebrospinal fluid. These manuscripts have also revealed detailed depictions of intricate neurosurgical procedures.

Last week, a group of historians reported in the journal PLOS ONE that they have found proof of a distinct form of brain surgery called angular notched trephination, which was carried out on a man in Israel over 3,000 years ago.

On its own, this data is astounding. The 15th century BC predates the development of morphine or antibiotics – and advanced equipment such as vital monitors, general anesthesia, and traditional operating rooms were nonexistent. (However, it may bring comfort to know that contemporary brain surgery is occasionally performed without general anesthesia as well.)

However, the knowledge of this ancient surgical technique is crucial in our endeavor to unveil a comprehensive timeline of medical progress throughout human history.

According to Rachel Kalisher, a doctoral candidate at Brown University and head of the team’s research, “We have evidence that trephination has been a widely practiced form of surgery for thousands of years. However, it is not as common in the Near East, where there are only about a dozen recorded instances of trephination in the entire region.”

Rachel Kalisher is currently working on site in Megiddo, Israel. She emphasized that there was much more tolerance and care in the past than commonly perceived. Evidence dating back to the time of Neanderthals demonstrates that people took care of each other, even in difficult situations. She acknowledges that there were still divisions based on gender and social class, but ultimately people were still people.

Essentially, trephination involves utilizing a drill – which could have been crafted from stone tool in the past – to create an opening in the skull for the purpose of treating head injuries or alleviating discomfort. Its name is sourced from the ancient Greek term “trypanon,” indicating “borer” or “auger.”

However, during the ancient times, the drilled hole was considered as the sole solution and hence it was considered as a permanent fix. This is the exact reason why researchers could find such distinct proof of trephination in their subject from the 15th century BC. Presently, the nearest alternative to trephination is craniotomy. Nonetheless, dissimilar to the ancient trephination, doctors conducting craniotomies aim to swiftly put back the drilled piece of skull in the original position.

Generally speaking, craniotomies are regarded as infrequent due to their high risk. They are commonly carried out to address aneurysms, remove brain tumors, or alleviate pressure in the brain for various other reasons. If you’re a fan of Grey’s Anatomy, you have probably witnessed a dramatized craniotomy at least once, maybe even dozens of times.

The main inquiry

One out of a pair of skeletons, interred with high-quality ceramics and other precious belongings beneath a privileged dwelling in Tel Megiddo, Israel, exhibited a rectangular opening measuring around 30 millimeters in the frontal part of its cranium.

According to the researchers, the square form is intriguing because there is still uncertainty regarding why some trephination remains are triangular, others are square, and some are circular. It is believed that these individuals were most likely siblings, with one dying at a young age, in their teenage years or early twenties. The other probably passed away between their twenties and forties.

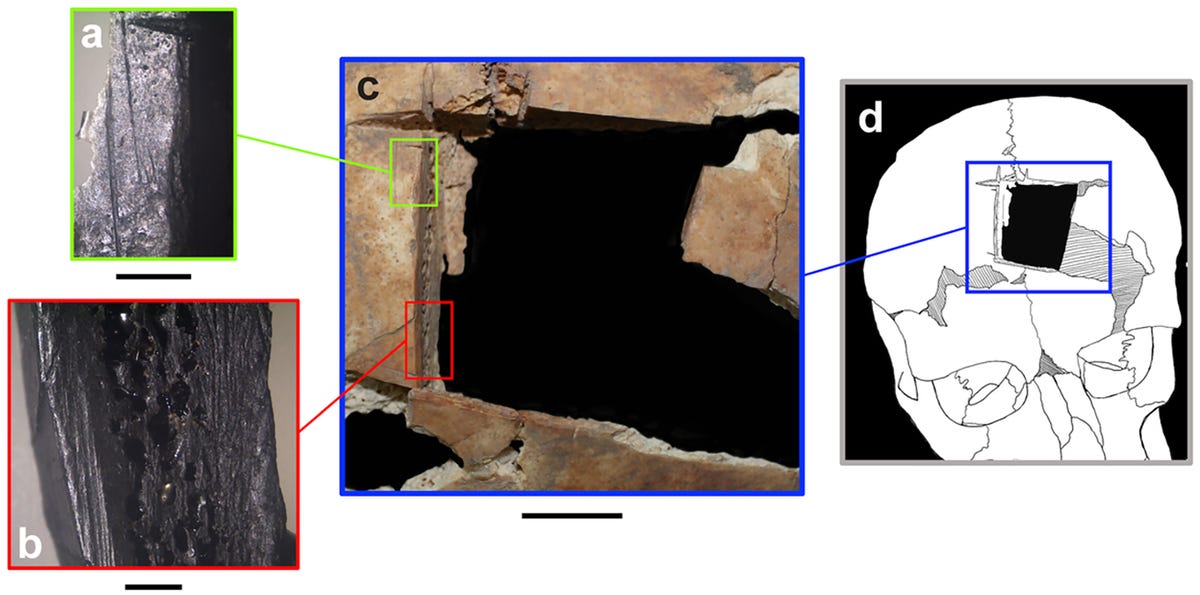

(A,B) Enhanced boundaries of the trephination, with a 2 millimeter reference line for each edge. (C) All four boundaries of the trephination, with a 1 centimeter benchmark line. (D) Reconstructed position of the trephination on the skull.

Kalisher et al., 2023, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0

According to Kalisher, one must be in an extremely problematic state to undergo trephination, i.e. the process of cutting a hole in one’s head. The author shows keen interest in thoroughly studying every instance of trephination in ancient times, and meticulously analyzing and drawing comparisons between the individual circumstances of every person who underwent the procedure.

It is intriguing that a person of high status required an invasive procedure during the 15th century. During that era, elite individuals typically had access to nutritious food, the best medical professionals, and were not required to work as much.

Hence, it is plausible that an elite individual could endure a severe ailment for a longer period compared to a non-elite person.

Consequently, the team pondered over what could have driven one of these wealthy brothers to undergo a frightening trephination procedure. Subsequently, the team identified some potential explanations.

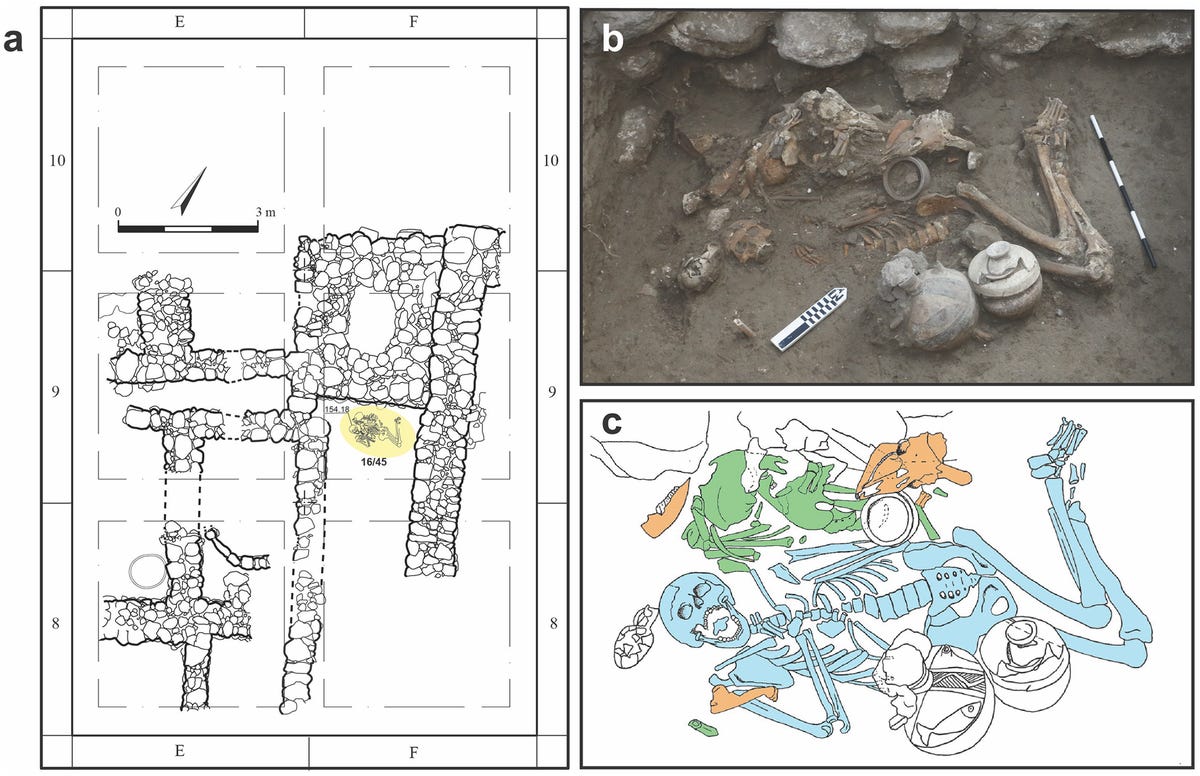

(A) The specific tomb is highlighted in yellow in the area where the remains were discovered. (B) An image of the burial site and the remains is presented. (C) A composite sketch illustrates one individual in blue and another in green.

In 2023, Kalisher et al. published a research article under the CC-BY 4.0 license in PLOS ONE. The study reported various skeletal abnormalities in the remains of two brothers, implying a possible iron deficiency anemia that could have affected their growth from childhood. Additionally, the older brother exhibited a cranial suture and an extra molar in the corner of his mouth, which Kalisher associated with a congenital disorder called Cleidocranial dysplasia. This rare condition is characterized by brittle and abnormally shaped bones.

Additionally, according to Kalisher’s analysis, around 33% of one skeleton and 50% of the other exhibit indications of porosity, lesions, and inflammation in the bone membrane, indicating that the potential cause of death for the brothers might have been an infectious ailment like tuberculosis or leprosy.

Kalisher stated that leprosy can transmit among families not only due to their proximity but also due to the influence of their genetic makeup on the vulnerability to this disease. Moreover, the identification of leprosy is challenging as it involves bone damage in different stages, and the sequence and intensity of these stages might vary across individuals.

Further investigation is necessary to fully decipher the events surrounding the unfortunate fate of the two brothers. However, as pointed out by Kalisher, one thing is clear: if the intention behind the angular notched trephination was to save the boy’s life, it failed to do so.

The team determined that the patient passed away within days, hours, or even minutes after the surgery.